Diseases & Conditions

What is elephant leg, cellulitis or lymphangitis in horses?

Stuart Davies BVSc MRCVS, explains what’s going on in this very painful condition

Cellulitis in horses (and lymphangitis in horses) may not be on an owner’s radar as a possible health condition that may affect their horse. However, once encountered, it will be remembered due to the sudden onset crippling pain, along with the concern of developing serious complications. So…. what is this condition also known as elephant leg?

Initially we must cover briefly some simplified dermatological (skin) anatomy of the horse. There are three layers to the skin:

- Epidermis: This is the most external surface of the skin. It presents a barrier between the deeper levels and the external environment.

- Dermis: a thick layer of connective tissue consisting of blood vessels, nerves, small lymphatic vessels, sweat and sebaceous glands

- Subcutis: consists of adipose tissue (fat) in addition to major lymphatic vessels

Cellulitis, lymphangitis – what is the difference?

Strictly speaking cellulitis in horses is a suppurative infection (production of pus) within the internal layers of the skin predominantly the subcutis¹ lymphangitis is inflammation/ infection of the lymph vessels. Lymph vessels are present throughout the body and are similar to veins, except they collect fluid from cells and return it to the body. However, the two are often interchangeable and sometimes indistinct.

The exact prevalence of the condition is unknown due to a lack of scientific literature however, it is a common occurrence in primary equine practice. Infection develops within the subcutaneous layers once there is a break in the epidermis, this is termed secondary cellulitis¹. If no wound or inciting cause is apparent this is termed primary cellulitis. The bacteria involved, Staphylococcus aureus, are usually found on the skin surface and multiply within the skin layers, once they have gained entry².

The inflammation of limb vessels leads to the accumulation of protein rich fluid causing lymphoedema (excess fluid within lymph vessels) and ultimately, interstitial oedema (fluid out of vessels). Infection can spread throughout the affected area to deeper structures and, in the worse affected cases can cause sepsis from spread to the rest of the body. While skin covers the entire surface of the body, horses appear to be predominantly affected on their limbs, more often a singular hindlimb.

Cellulitis can be a rapidly developing condition with an acute onset lameness and limb swelling. The Additional treatments that can be performed include:

Cold therapy in the form of cold hosing. This can be useful in the initial stages of inflammation. Cryo-therapy studies predominantly use ice however a simple hose is available in most places. Reducing the skin’s temperature provides analgesia (pain relief) by reducing nerve conduction of pain signals, while it also reduces inflammation by causing vessel changes, hypometabolism and a reduction in inflammatory mediators⁴.

Excessive wetting of the skin should be avoided due to reducing the skin’s immune barrier.

Limb bandaging can assist in preventing further fluid accumulation by the misfunctioning lymph vessels. However, in the initial stages the condition is so painful, that bandaging will not be tolerated.

Walking the horse as soon as is possible assists in moving lymph through vessels. Manual lymph drainage massage has been long performed in the treatment of people with lymphoedema. This is now being recognised in horses with reports that massage helps increase fluid drainage and breaks down scar tissue

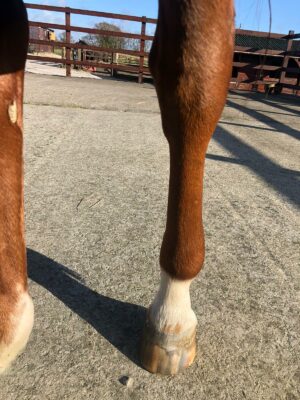

Figures 1a, 1b. A mild cellulitis and leg filling due to a small wound (pictured). While the owners waited for the vet to arrive to administer antibiotics and anti-inflammatories the leg was cold hosed, and the horse walked for 15 minutes.

Treatment

As mentioned above, rapid treatment for a horse with a swollen leg (as pictured) is needed to reverse the inflammation within the skin and lymphatic vessels. The greater the degree or longer duration of the limb swelling leads to an increased risk of the limb remaining enlarged from damage to the elastin³.After a thorough exam, and any diagnostic tests required, vets will usually administer broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics in conjunction with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, such as phenylbutazone and flunixin. The discomfort exhibited by patients can be so grave that further pain relief is required, sometimes necessitating referral to a hospital facility.

Figures 2a, 2b, 2c: A bad case of lymphangitis in horses. The leg increased in diameter to such an extent that serum leaked from the skin. Treatment involved an intensive course of intravenous antibiotics, steroids and anti-inflammatories.

So how does an owner prevent their horse being affected by cellulitis?

Try to avoid excessive wetness of the skin – this increases the risk of damage to the surface. If limbs are to be washed, then they should be thoroughly towel dried

- Maintain good grooming kit hygiene to reduce the bacterial burden that your brushes may be passing onto the skin. If leaving mud to dry on legs, do not brush too aggressively to avoid trauma

- Treat any skin wounds with topical antimicrobials If stabled for prolonged periods, ensure limbs are stable bandaged or regular exercising is performed

- Treat chorioptes (feather mites) and allergies to prevent the horse causing self-inflicted trauma to its legs

Related reading:

Help my horse has mud fever Hibiscrib – are you using it correctly Wet skin conditions What is lymphangitis?

References

- Scott, D. W. and Miller, W. H. (2003) Equine dermatology. Saunders (Online access with purchase: Elsevier (Veterinary Medicine pre-2007)). Available at: https://search-ebscohost-com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00003a&AN=lvp.b2598301&site=eds-live&scope=site (Accessed: 14 February 2021)

- Fjordbakk, C. T., Arroyo, L. G. and Hewson, J. (2008) ‘Retrospective study of the clinical features of limb cellulitis in horses (63)’, Veterinary record : journal of the British Veterinary Association, 162(8), pp. 233–236. doi: http://veterinaryrecord.bvapublications.com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/

- De Cock, H.E., Affolter, V.K., Farver, T.B., van Brantegem, L., Scheuch, B. and Ferraro, G.L. (2006) Measurement of skin desmosine as an indicator of altered cutaneous elastin in draft horses with chronic progressive lymphedema. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 4, 67‐72. Scott, W.D. and Miller, W.H. (2003) Bacterial skin diseases: staphylococcal infections. In: Equine Dermatology , 1st edn., Ed: W.D. Scott and W.H. Miller, Saunders, St. Louis. pp 216-227.

- Roszkowska, K. et al. (2018) ‘Whole body and partial body cryotherapies – lessons from human practice and possible application for horses’, BMC Veterinary Research, 14(1), pp. 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1679-6.

- Powell, H. and Affolter, V.K. (2012), Combined decongestive therapy including equine manual lymph drainage to assist management of chronic progressive lymphoedema in draught horses. Equine Veterinary Education, 24: 81-89. https://doi-org.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/j.2042-3292.2011.00311.x

- Vyetrogon, T. and Dubois, M.-S. (2019) ‘Perisuspensory abscessation in eight horses with hindlimb cellulitis’, Equine Veterinary Education, 31(12), p. e66. doi: 10.1111/eve.12996