Diseases & Conditions, Featured, Nutrition, Veterinary

Atypical myopathy

Briony Witherow, discusses the latest advice and research into atypical myopathy

Atypical myopathy (also known as sycamore myopathy) was first identified back in the 1940s, however, prevalence in recent years appears to be on the rise. While ordinarily it is factors of more intensive management (stabling, rugging and alike) that pose risk to our horse’s welfare, this risk rather frustratingly exists in the pastures in which our horses graze. While many poisonous plants can be dug up, fenced off or even chemically controlled where needed, sycamore seeds and seedlings can travel long distances making pasture contamination often hard to predict and manage.

How can horse owners maintain turnout while also managing the risk of atypical myopathy?

Much of the solution lies in increasing our awareness of the disease; increasing our knowledge of the offending trees and how to correctly distinguish them; and knowing how to practically moderate risk in situations where alternative turnout is not available, or we don’t have full control of pasture management. Below we discuss what atypical myopathy is, it is necessary to provide you with the tools to identify hazardous trees and, how to deal practically with pasture which may be contaminated.

What is atypical myopathy?

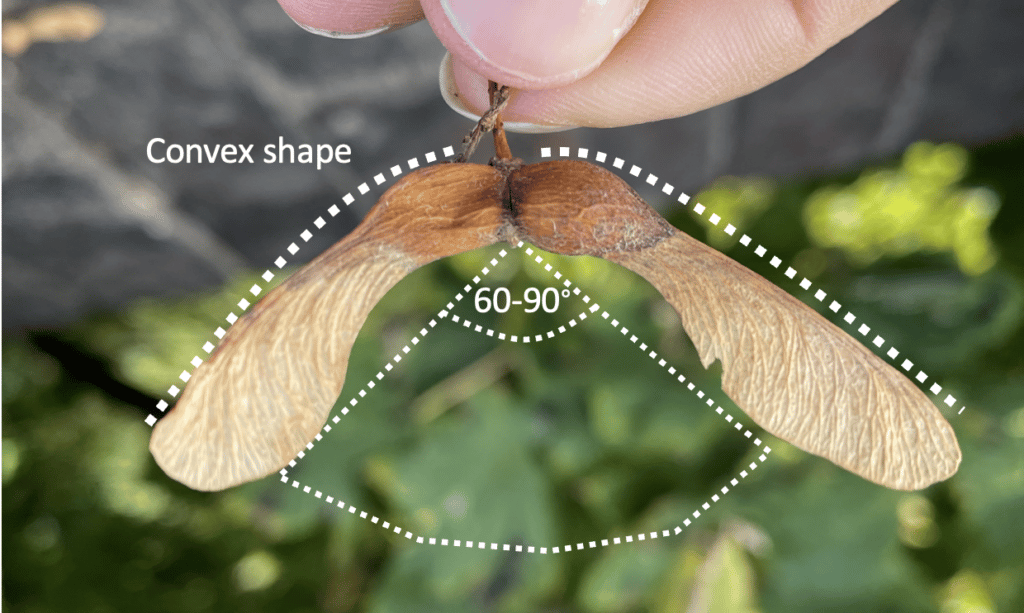

Equine atypical myopathy is defined as a severe intoxication affecting grazing horses1 caused by the consumption of seeds (samaras, winged seeds, or “helicopters”) or seedlings of acer tree species (Acer pseudoplatanus (known as sycamore in the UK and EU2 and sycamore maple in North America) and Acer negundo (Box Elder in the USA)).

Intoxication typically occurs in autumn (76%3) and spring (24%3) the ingestion of seeds or seedlings introducing cyclopropylamino acids, hypoglycin A (HGA) and methylenecyclopropylglycine (MCPG) into the horse’s system4. The action of these compounds and their metabolites prevents cells from using energy, affecting the function of skeletal, respiratory, and cardiac muscles5.

The disease develops quickly – a significant decline in condition often seen in as little as 6-12 hours, and is often fatal6. In some cases, a lag of four or more days can exist from ingestion of the seed or seedling and the onset of clinical signs7 and, in some cases symptoms are not apparent8.

Common symptoms of atypical myopathy

- Reluctance to moveb

- Lethargic/quiet demeanour

- Muscle weaknessb

- Stiffnessb often characterised as acute rhabdomyolysis unrelated to exercise

- Normal body temperature (Normothermiab)

- Sweatingb

- Depressionb

- Dark red/brown urine (Myoglobinuria

- Recumbencyb

- Distended bladderb

- Muscle tremors or twitches (fasciculationb )

- Congested mucous membranesb

Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis of the atypical myopathy is often made through clinical history, signs and symptoms and laboratory findings (blood and urine analysis).

Atypical myopathy has a high mortality rate (74% average6 with rates in the UK slightly lower at 61%10) this does vary slightly between countries and years. Survival rate appears highly dependent on swift diagnosis and treatment11. There is currently no antidote available to counter the toxin – so veterinary intervention focusses on pain management, promoting fluid intake and vitamin and mineral provision1, 12

Research investigating factors associated with survival of atypical myopathy show that patients which remain standing most of the time; have normal body temperature, mucous membranes, and defecation along with vitamin and antioxidant therapy, are more likely to have positive outcome13,6,14.

Assessing the risk of atypical myopathy

Learn which trees contain harmful toxins

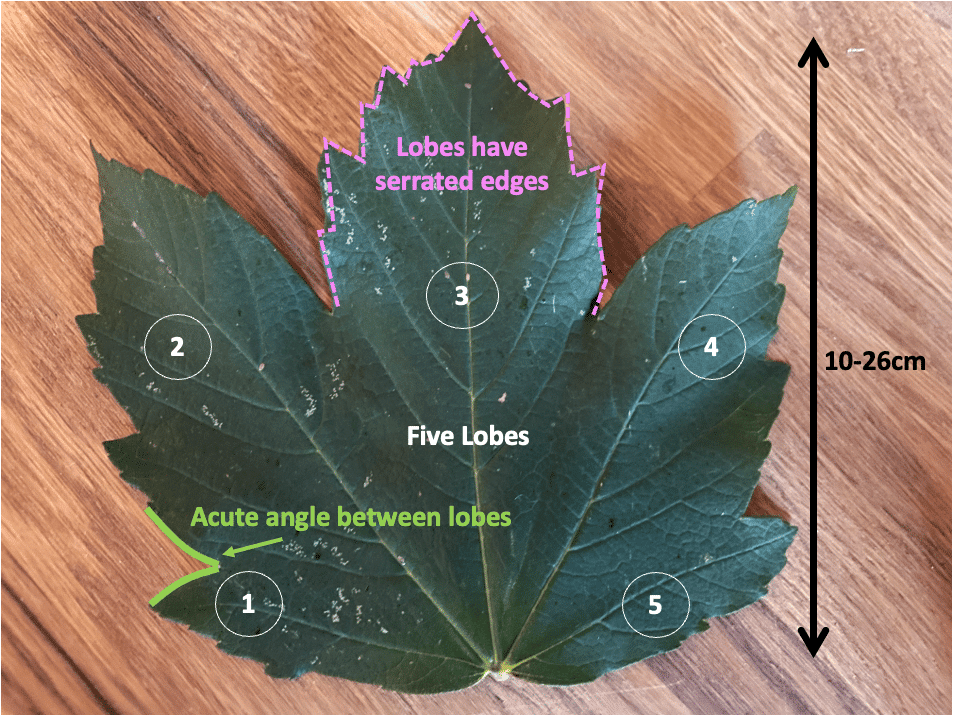

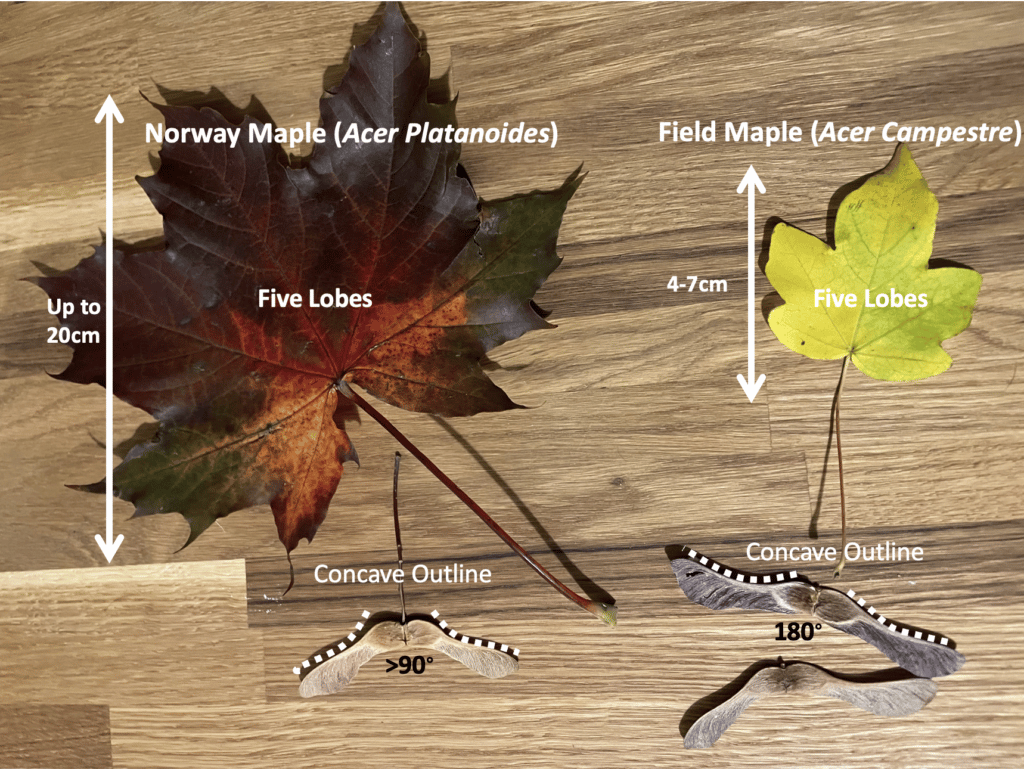

Not all acer tree species are thought to contain detrimental toxins, however distinguishing the differences between these is not always easy (See fig 1 and 2). Becoming familiar with reportedly harmful acer species like Acer pseudoplatanus and how these differ from Acer Campestre (Field Maple) and Acer Plantanoids (Norway Maple) (see figure 3) is key to prevention15.

Time of year

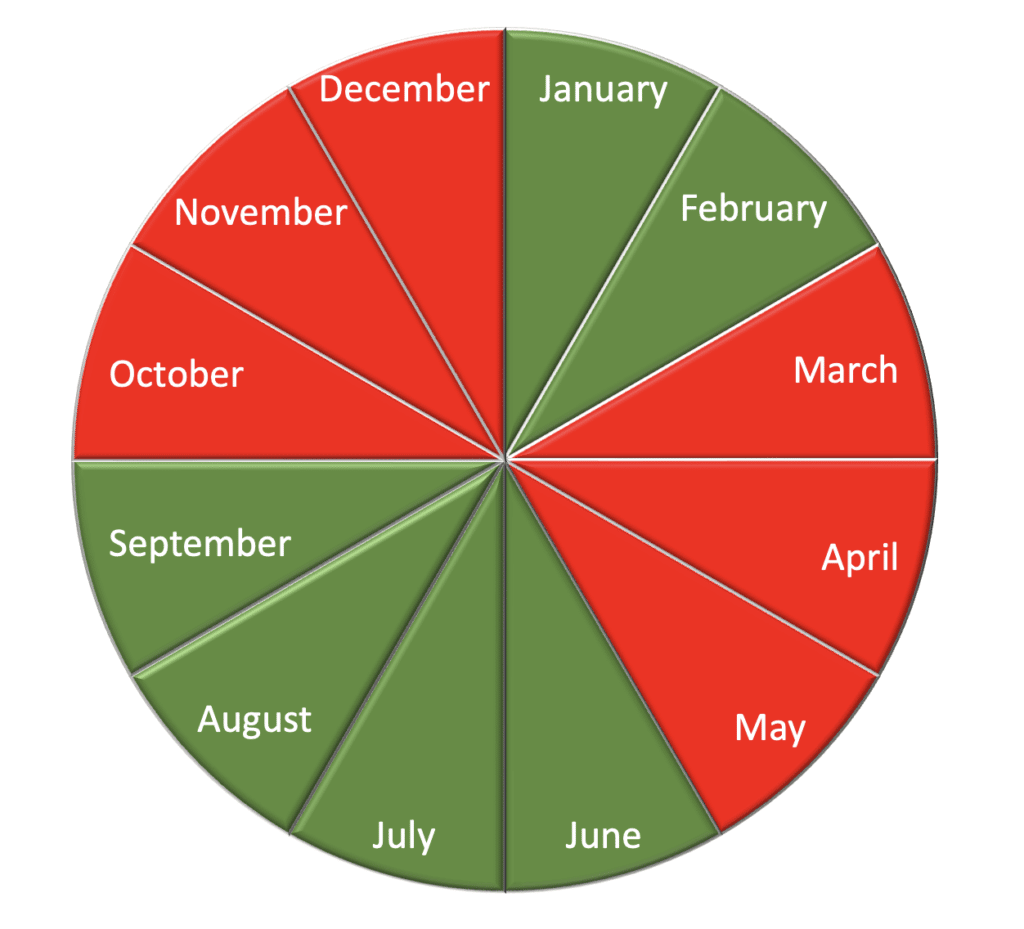

94% of cases have been reported to occur over two 3-month periods, starting in October (seed ingestion) and in March (seedling ingestion).

Toxicity

Time of year

94% of cases have been reported to occur over two 3-month periods, starting in October (seed ingestion) and in March (seedling ingestion).

Rough estimates suggest that intake of between 43-98 helicopter pairs (seeds) or 50-200 juvenile seedlings would be toxic for a 500kg horse, with worst case estimates lower still16, 17, 18.

Prevention

Managing the risk

When it comes to managing the risk of atypical myopathy there are two key areas of management, the pasture, and the horse itself. We consider both below:

The first step in prevention is to identify any sycamore acer trees with proximity to or, bordering pasture and ideally, avoid grazing horses in these fields completely or, where this isn’t practicable take precautions.

If grazing fields within proximity of poisonous sycamore trees, the following management can be undertaken to reduce risk:

- Fence the trees and surrounding areas off (consider that seeds can be blown a long distance (>200m) from the tree itself)19.

- Reduce turnout time according to weather conditions, reducing to <6 hours per day during high-risk periods (stabling during bad weather (particularly wet, cold and/or windy). Where feasible, only graze affected pasture in the summer or winter months.

- Avoid over-stocking pasture to ensure there is sufficient grazing for all horses

- Ensure horses are fed prior to turnout. Provide supplementary feeds including toxin-free forage, vitamins, minerals, and access to salt3.

- Remove seeds with paddock vacuums

- Do not feed from the floor and avoid feeding near tree lines

- Undertake regular inspection of fields to ensure seeds have not blown in from sycamore trees in neighbouring fields or properties. Additional inspections following stormy weather or felling of trees is advisable.

- Do not use contaminated pastures to produce hay or haylage20.

- Interventions such as the application of herbicides or mowing do not seem effective in reducing level of HGA20.

- Provide access to mains water rather than natural sources of water3,13. Consider trough placement in fields – avoid the tree line and clean regularly. HGA is water soluble and therefore may pass from plants to water through direct contact18.

- Avoid spreading of manure or harrowing that may further contaminate pasture.

- Some labs and veterinary practices are now able to test leaves, seeds and seedlings to identify whether or not they contain HGA; this may be advisable where total avoidance is not an option.

Future research

To date a few papers have reported that there may be association between certain faecal microbiota and horses affected with atypical myopathy, indicating this as an area for further investigation21. Further studies investigating the differences between affected horses and healthy co-grazing horses may yet help to explain why some horses appear predisposed22.

Take home points

- If you are concerned that your horse may have ingested sycamore seeds or seedlings and is showing signs of atypical myopathy, contact your vet immediately.

- If a case of atypical myopathy is suspected, remove all horses from the pasture and discuss testing non-symptomatic horses with your vet.

- Make sure you are familiar with the trees within and surrounding your horse’s pasture. Try to identify any acer varieties and differentiate between them.

Walk your fields regularly during high-risk months and employ management practices to promote prevention.

Further reading: Atypical myopathy in hay

References

- Votion, D-M. (2016) Atypical myopathy: an update. In Practice, 38 (5): 241-246

- Gonzalez Medina, S., Hyde, C., Lovera, I., Piercy, R.J. (2018) Detection of equine atypical myopathy-associated hypoglycin A in plant material: optimisation and validation of a novel LC-MS based method without derivatisation. PLOS ONE, 13 (7): e0199521. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199521

- Votion, D-M., François, A.C., Kruse, C., Renaud, B., Farinelle, A., Bouquieaux, M-C., Marcillaud-Pitel, C., Gustin, P. (2020) Answers to the frequently asked questions regarding horse feeding and management practices to reduce the risk of atypical myopathy. Animals, 10 (2):365. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020365

- Bochnia, M., Sander, J., Ziegler, J., Terhardt, M., Sander, S., Janzen, N., Cavalleri, J.M., Zuraw, A., Wensch-Dorendorf, M., Zeyner, A. (2019) Detection of MCPG metabolites in horses with atypical myopathy. PLoS ONE, 14, e0211698.

- Votion, D.M., Van Galen, G., Sweetman, L., Boemer, F., De Tullio, P., Dopagne, C., Lefère, L., Mouithys-Mickalad, A., Patarin, F., Rouxhet, S., van Loon, G., Serteyn, D., Sponseller, B.T., Valberg, S.J. (2014) Identification of methylenecyclopropyl acetic acid in serum of European horses with atypical myopathy. Equine Vet. J. 46, 146–149

- van Galen, G., Saegerman, C., Marcillaud-Pitel, C., Patarin, F., Amory, H., Baily, J.D., Cassart, D., Gerber, V., Hahn, C., Harris, P., Keen, J.A., Kirschvink, N., Lefere, L., McGorum, B., Muller, J.M., Picavet, M.T., Piercy, R.J., Roscher, K., Serteyn, D., Unger, L., van der Kolk, J.H., van Loon, G., Verwilghen, D., Westermann, C.M., Votion, D.M. (2012) European outbreaks of atypical myopathy in grazing horses (2006-2009): determination of indicators for risk and prognostic factors. Equine Vet J. 44(5):621-5. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2012.00555.x

- Rendle, D. (2016) ‘Atypical’ myopathy— hypoglycin toxicity in horses. Livestock, 21(3):188–193. https://doi.org/10.12968/live.2016.21.3.188

- van Galen, G., Serteyn, D., Amory, H., Votion, D.M. (2008) Atypical myopathy: new insights into the pathophysiology, prevention and management of the condition. Equine Vet Educ. 20(5):234–238. https://doi.org/10.2746/095777308X299103

- Votion, D.M., Linden, A., Saegerman, C., Engels, P., Erpicum, M., Thiry, E., Delguste, C., Rouxhet, S., Demoulin, V., Navet, R., Sluse, F., Serteyn, D., van Galen, G., Amory, H. (2007) History and clinical features of atypical myopathy in horses in Belgium (2000–2005). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 21, 1380–1391.

- González-Medina, S., Ireland, J.L., Piercy, R.J., Newton, J.R. and Votion, D.M. (2017) Equine atypical myopathy in the UK: Epidemiological characteristics of cases reported from 2011 to 2015 and factors associated with survival. Equine Vet J, 49: 746-752. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj.12694

- Dunkel, B., Ryan, A., Haggett, E. and Knowles, E.J. (2020) Atypical myopathy in the South-East of England: Clinicopathological data and outcome in hospitalised horses. Equine Vet Educ, 32: 90-95. https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.12895

- Fabius, L.S. and Westermann, C.M. (2018) Evidence-based therapy for atypical myopathy in horses. Equine Vet Educ, 30: 616-622 https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.12734

- van Galen, G., Serteyn, D., Amory, H., Votion, D.M. (2008) Atypical myopathy: new insights into the pathophysiology, prevention and management of the condition. Equine Vet Educ. 20(5):234–238. https://doi.org/10.2746/095777308X299103

- Finno, C.J., Valberg, S.J., Wunschmann, A. and Murphy, M.J. (2006) Seasonal pasture myopathy in horses in the midwestern United States: 14 cases (1998–2005). J. Am. Vet. Med. Ass. 229, 1134-1141.

- Westermann, C.M., van Leeuwen, R., van Raamsdonk, L.W., Mol, H.G. (2016) Hypoglycin A Concentrations in Maple Tree Species in the Netherlands and the Occurrence of Atypical Myopathy in Horses. J Vet Intern Med. 30(3):880-4. doi: 10.1111/jvim.13927

- Blake, O.A., Bennink, M.R., Jackson, J.C. (2006) Ackee (Blighia sapida) hypoglycin A toxicity: dose response assessment in laboratory rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 44(2):207– 213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2005.07.002

- Valberg, S.J., Sponseller, B.T., Hegeman, A.D., Earing, J., Bender, J.B., Martinson, K.L., Patterson, S.E., Sweetman, L. (2013) Seasonal pasture myopathy/atypical myopathy in North America associated with ingestion of hypoglycin A within seeds of the box elder tree. Equine Vet J. 45(4):419–426. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2012.00684.x

- Votion, D-M., Habyarimana, J.A., Scippo, M-L., Richard, E.A., Marcillaud-Pitel, C., Erpicum, M., and Gustin, P. (2019) Potential new sources of hypoglycin A poisoning for equids kept at pasture in spring: a field pilot study. Vet Record, 184 (24): 740-740

- Katul, G.G., Porporato, A., Nathan, R., Siqueira, M., Soons, M.B., Poggi, D., Horn, H.S., Levin, S.A. (2005) Mechanistic analytical models for long-distance seed dispersal by wind. Am. Nat. 166, 368–381.

- González-Medina, S., Montesso, F., Chang, Y.M., Hyde, C., Piercy, R.J. (2019) Atypical myopathy-associated hypoglycin A toxin remains in sycamore seedlings despite mowing, herbicidal spraying or storage in hay and silage. Equine Vet J. 51(5):701-704. doi: 10.1111/evj.13070.

- Wimmer-Scherr, C., Taminiau, B., Renaud, B., van Loon, G., Palmers, K., Votion, D., Amory, H., Daube, G., Cesarini, C. (2021) Comparison of Fecal Microbiota of Horses Suffering from Atypical Myopathy and Healthy Co-Grazers. Animals, 11, 506. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ani11020506

- Wouters, C.P., Toquet, M.P., Renaud, B., François, A.C., Fortier-Guillaume, J., Marcillaud-Pitel, C., Boemer, F., De Tullio, P., Richard, E.A, Votion, D.M. (2021) Metabolomic Signatures Discriminate Horses with Clinical Signs of Atypical Myopathy from Healthy Co-grazing Horses. J Proteome Res. 20(10):4681-4692. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00225.