Behaviour, Diseases & Conditions, Featured, Rehab, Skeletal

My horse has kissing spines – is surgery the only option?

Edward Busuttil discusses the most common causes of back pain in horses and, why conditioning of horse and rider is vital

It is well documented that horses with overriding dorsal spinous processes (ODSP), more commonly called kissing spines, do not necessarily show pain ¹ ² therefore, radiographic findings may be incidental. This does not however, prevent pre-purchase radiographs of the thoracic vertebrae being routinely carried out – a procedure generally led by the potential purchaser, usually due to a negative past experience.

Back pain in horses can present in a number of ways, in my experience, owners generally report resentment to being saddled, reluctance to move forward under saddle and/or bucking and agitation when the back is palpated. Confirmation is generally obtained with radiographs of the thoracolumbar vertebrae and ultrasonography of the vertebral joints. The size and symmetry of the multifidus muscle should be noted, as asymmetry between the left and right side is indicative of pathology at that level³.

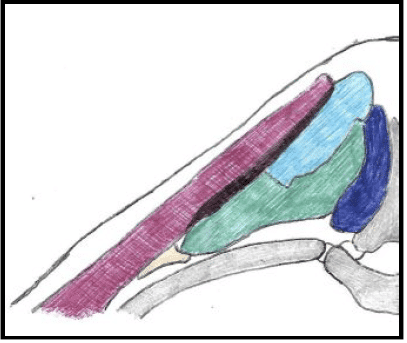

Figure 1: Drawing of the cross-section of the left side of a horse’s back epaxial muscles within the thoracic region

- Grey – Bones (vertebra and rib)

- Dark Blue – Multifidus muscle Light blue – spinal muscle

- Green – Longissimus dorsi muscle

- Black – Thoracic rhomboid muscle

- Yellow – Iliocostal muscle

- Red – Latissimus dorsi muscle

Local anaesthesia (nerve block) of the ODSP is not commonly carried out. This is because the horse is generally heavily sedated during radiography to minimise risk to staff exposure to radiation and, to keep the horse quiet and calm during the process and the vicinity to large expensive equipment.

If clinical suspicion does not correlate with diagnostic findings, local anaesthetic may be subsequently infiltrated into the area of pain, only after ensuring the safety of the rider before and after blocking. Although nuclear scintigraphy (bone scan) can be useful in indicating whether there are increased bone changes within the dorsal spinous processes and therefore, active remodelling and pain, it is very rarely indicated due to cost implications.

Treatment choice is generally driven by owner finance and insurance policies, as well as their past experience and research. There is often an initial false expectation that one-off medication and manipulation alone can make the horse’s back pain-free forever more. When results are taking longer to obtain, or there is a lack of owner compliance in management when returning to work, there is a push for ODSP surgery as a quick resolution, generally to get the horse out competing sooner or, before the time-dependent insurance policy (generally a year after the start of investigation) runs out.

Thoroughbred racing

In my experience working as a vet, surgery to resolve pain associated with ODSP has been overrepresented in off the track (retired) Thoroughbred racehorses, particularly in horses which have steeplechased. Having discussed the procedure with surgeons in the UK, USA, Ireland, Australia and Hong Kong, there is a general agreement that surgery is not performed on horses that race on the flat. However, it does occur infrequently in horses competing in steeplechase – 50% of all steeplechase races occur in the UK and Ireland. Whereas professional steeplechasing is commonly termed National Hunt racing, amongst amateur riders it is called point-to-point. National Hunt horses progress from racing over bumpers, to hurdles and finally fences. The races are generally at least 2 miles long and over at least 8 obstacles.

What are the biomechanics of the vertebral column associated with racing?

Racehorses are trained to gallop around a course, as quickly as possible while maintaining their stamina. The gallop is a four-beat gait within which there is active extension and flexion of the thoracolumbar spine (as opposed to a trot, where both actions are passive and, due to bounce created by the horse’s abdomen).

During hindlimb suspension, there is an elevation of the neck and engagement of the hindlimbs, together assisting thoracolumbar flexion, which is carried out through simultaneous contraction of the abdominal muscles. Conversely, during hindlimb propulsion, the neck is passively and actively lowered, and extension is present through the thoracolumbar spine via concentric contraction of the erector spinae muscle.

Jumping involves a take-off, airborne and landing phase, each having biomechanical implications on the vertebral column⁴.

This does not take into account the increased strains associated with running at high speeds, having to accelerate again after landing, the different footing that the horse and rider need to consider and, the biomechanics associated with flexion and extension of the limbs.

It is therefore, easy to understand the increased strain, which the vertebral column is under during the athletic career of Thoroughbreds, particularly those that steeplechase.

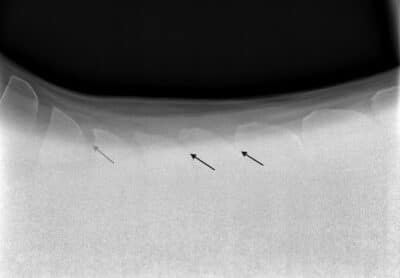

Figure 2: The 2 black arrows represent areas of decreased interspinous space between two dorsal spinous processes; the grey arrow represents a normal interspinous space

Why does back pain become more of an issue once the horse has retired?

As discussed earlier, off the track Thoroughbreds represent a large proportion of horses, which general practitioners all around the world examine due to back pain. Although this could be due to the biomechanics associated with racing and training and, the active flexion and extension of the vertebral column under strain leading to more pathological issues as the horse ages, racehorses are generally retired from racing because they are no longer performing at the desired level. A loss of condition and muscle tone may also exacerbate other underlying issues.

Certain variables such as the weight and experience of a new rider in a new career, may be difficult to manage, whereas other variables cannot be changed, these include genetic predisposition and other previous musculoskeletal issues for which the horse has been treated. Appropriate saddle selection and return to work can however, be managed carefully to ensure that the back is adequately strengthened.

Saddles

Correct saddle fit is key to improving the riding experience for both the horse and rider, with the saddle’s kinematics having a significant influence on the way the horse moves⁵. A poor-fitting saddle will negatively affect the biomechanics of the back and its muscular development, promoting muscular wastage and eliciting pain⁶, due to irritation of the spinal nerves. It will also prevent appropriate increase in dimensions of the back, which occurs during exercise⁷.These effects can be worsened by a rider that is poorly balanced or, too heavy or tall for the horse they are riding⁸.

Saddle fitting is challenging, even though there is general agreement between different qualified saddlers⁹. Regular checking of saddle fit should be routinely scheduled to measurable changes in the shape of the horse’s back demonstrated at two-month intervals¹⁰.

Saddles with a narrow tree tend to tip the seat backwards, whereas those with a wide tree tend to tip the rider forwards, also resulting in rider discomfort¹¹. Asymmetric saddles are also a common problem, resulting in unequal pressure over the horse’s back¹². Although the rider may be tempted to insert a thicker pad underneath the saddle, which may result in an initial improvement, the pad might worsen the saddle fit or result in the formation of new pressure points, instead of resolving them⁷.

It is therefore essential that the saddle the new owner plans to use is assessed at the very start of their relationship with the horse and, at regular intervals thereafter. Helping the new owner understand the effects of an ill-fitting saddle is possibly more important than the rehabilitation work that is undertaken down the line, as consistent discomfort under the saddle will result in poor muscle development.

Return to work

The return to work of any equine patient depends on the degree of pathological change and, owner compliance, through their expectations, finances and the time that they can put into rehabilitating their horse. It is essential to have a good understanding of the issues present within the horse’s back, to be able to give a realistic prognosis of the level of work to which the horse can return. Equally, if the owner is unable to commit to certain elements of a strengthening and conditioning plan, they must understand that it will take longer and require more hands-on time to reach their goals. If the owner does not have access to transportation and cannot commit to rehabilitation livery, then hydrotherapy, or use of certain facilities may not be possible; this must be taken into consideration when formulating a plan.

The success of the horse’s return to work will depend on owner compliance, as well as on the cooperation of the veterinarian and other para-professionals, including chartered physiotherapists, chiropractors and saddlers, involved in the case.

Pain inhibition

As most horses initially present due to back pain, inhibition is key to decrease inflammatory markers and to create an environment within which normal biomechanics of the back can resume.

Pain due to saddle fit should be ruled out.

A number of options are available:

- Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Mesotherapy ¹³

- Local infiltration with corticosteroids

- Extracorporeal Shockwave¹⁴

- Laser Therapy ¹⁵

- Electro-acupuncture¹⁶

Other modalities have also been suggested to assist with relief of back pain, however, the scientific evidence available thus far is unflattering and therefore, I would be very hesitant in suggesting the following modalities for treatment of back pain.

- Pulsed electromagnetic fields¹⁷

- Whole Body Vibration¹⁸

- Therapeutic Ultrasound ¹⁹

Every treatment option has limitations and cost implications but, a reduction of pain can help the horse work in a correct way to enhance muscle development.

Chiropractic care

Although chiropractic care alone does not appear to result in an inhibition of pain¹⁵, it has been shown to increase vertebral sagittal movement (flexibility), improve pelvic rotational symmetry and, to help provide a more flexed thoracic back for a period of at least 3 weeks²⁰. In my opinion, this means that once pain inhibition has been achieved, chiropractic care could be seen as a useful modality to provide biomechanical stability as the horse is brought back into work.

Reintroducing work

After a period of rest, to assist with the horse’s locomotion, coordination and to reduce its apprehension of pain, or as part of a warming up, or cooling down programme, mobilisation and stretching can be a useful tool in rehabilitating horses with thoracolumbar pain. Active mobilisations, which can assist with ODSPs include dorsoventral and lateral flexion of the caudal neck, sternal lifts, lateral tail pulls, wither pulls and pelvic tucks; showing the owner how to properly perform these mobilisations is key to avoid technical incompetence.

Dynamic mobilisation exercises alone have been shown to increase the cross-sectional area of the multifidus muscle over a three-month period ²¹. The same exercises have been shown to improve the probability of horses, which undergo colic surgery returning to the same level of work within a year, if they can be implemented properly from 4 weeks after the emergency procedure²².

Three main steps should be followed when planning rehabilitative care for the back²³.

- Restricting the lifting and extension of the head and neck to promote opening of the interspinous space, thus encouraging strengthening of the flexors (rectus and internal oblique, as well as the psoas muscle, particularly in the lumbar region). This will also lead to relaxation of the paravertebral muscles as they lengthen.

- Progressively engage the hindlimb muscles involved in impulsion, once the abdominal muscles have been adequately toned, to maintain lumbar flexion.

- Reinforce the point of equilibrium, thus, in time, encouraging harmonious collaboration between the muscles dorsal and ventral to the vertebral column, helping to create a shorter turning circle.

Exercise plans should be individualised, based on diagnostic findings and owner compliance. A cookbook, one-size fits all approach could be dangerous – while some exercises might be beneficial for back pain, they may predispose the horse to other issues, based on their clinical history. It is also worth remembering that a lot of racing Thoroughbreds might not carry out much schooling throughout their career and therefore, it might be more difficult to instil that into a programme, which the horse can complete.

Long reining with a lowered neck has been shown to induce flexion of the thoracic region and extension in the lumbar region²⁴, thus reducing pressure between the ODSPs. This therefore, puts the horse in a pain relieving position and results in elongation of the erector spinae and multifidus muscles, which helps to counter the reflex muscle spasm occurring with ODSPs²⁵.

This activity also strengthens the core muscles and improves the flexibility of the vertebral column, including lateroflexion between the 9th and 14th thoracic vertebrae. However, it can lead to excessive tension on the supraspinous ligament and compression of the vertebral bodies, particularly in the lower cervical spine²⁵. Exercises that lower the neck should be used cautiously, as the cranial weight shift can exacerbate pre-existing problems in the horse’s front limbs.

Very limited information is available regarding the use of treadmills, particularly water treadmills, during the rehabilitation of horses with back pain. In my personal experience, I have found that utilising a water treadmill twice a week for a three-week period can be very beneficial in suitably strengthening the epaxial musculature. Although scientific evidence is not yet available I have in practice, found that horses following this routine have an increase in cross-sectional area of the multifidus muscle within a few weeks. Hydrotherapy can also be useful in conditioning the horse, to ensure that it is ready for the increased demands of ridden work.

Conclusion

Every case of back pain due to ODSPs is different and requires different management. When the owner can commit time into strengthening their horse’s core and back, surgery can hopefully be avoided. Appropriate cooperation of veterinarians, physiotherapists, saddlers and chiropractors is essential to provide the best possible outcome.

References

- Jeffcott, L., 1980. Disorders of the thoracolumbar spine of the horse – a survey of 443 cases. Equine Veterinary Journal, 12(4), pp.197-210.

- Jeffcott, L., 1979. Radiographic Examination of the Equine Vertebral Column. Veterinary Radiology, 20(3-6), pp.135-139.

- Stubbs, N., Riggs, C., Hodges, P., Jeffcott, L., Hodgson, D., Clayton, H. and McGowan, C., 2010. Osseous spinal pathology and epaxial muscle ultrasonography in Thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 42, pp.654-661.

- Denoix, J., 2013b. Biomechanical analysis of landing. In: J. Denoix, ed., Biomechanics and Physical Training of the Horse, 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp.109-184.

- Mackechnie-Guire, R., Mackechnie-Guire, E., Fisher, M., Mathie, H., Bush, R., Pfau, T. and Weller, R., 2018. Relationship Between Saddle and Rider Kinematics, Horse Locomotion, and Thoracolumbar Pressures in Sound Horses. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 69, pp.43-52.

- Von Peinen, K., Wiestner, T., Von Rechenberg, B. and Weishaupt, M., 2010. Relationship between saddle pressure measurements and clinical signs of saddle soreness at the withers. Equine Veterinary Journal, 42, pp.650-653.

- Grieve, L., Murray, R. and Dyson, S., 2015. Subjective analysis of exercise-induced changes in back dimensions of the horse: The influence of saddle-fit, rider skill and work quality. The Veterinary Journal, 206(1), pp.39-46.

- Dyson, S., Ellis, A., Mackechnie‐Guire, R., Douglas, J., Bondi, A. and Harris, P., 2019. The influence of rider:horse bodyweight ratio and rider‐horse‐saddle fit on equine gait and behaviour: A pilot study. Equine Veterinary Education.

- Guire, R., Weller, R., Fisher, M. and Beavis, J., 2017. Investigation Looking at the Repeatability of 20 Society of Master Saddlers Qualified Saddle Fitters’ Observations During Static Saddle Fit. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 56, pp.1-5.

- Greve, L. and Dyson, S., 2014. A longitudinal study of back dimension changes over 1 year in sports horses. The Veterinary Journal, 203(1), pp.65-73.

- Greve, L. and Dyson, S., 2015. Saddle fit and management: An investigation of the association with equine thoracolumbar asymmetries, horse and rider health. Equine Veterinary Journal, 47(4), pp.415-421.

- Arruda, T., Brass, K. and De La Corte, F., 2011. Thermographic Assessment of Saddles Used on Jumping Horses. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 31(11), pp.625-629.

- Denoix, J. and Dyson, S., 2003. Thoracolumbar spine. In: M. Ross and S. Dyson, ed., Diagnosis and Management of Lameness in the horse, 1st ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, pp.509-521.

- Trager, L., Funk, R., Clapp, K., Dahlgren, L., Werre, S., Hodgson, D. and Pleasant, R., 2019. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy raises mechanical nociceptive threshold in horses with thoracolumbar pain. Equine Veterinary Journal, 52(2), pp.250-257.

- Haussler, K., Manchon, P., Donnell, J. and Frisbie, D., 2020. Effects of Low-Level Laser Therapy and Chiropractic Care on Back Pain in Quarter Horses. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 86, p.102891.

- Xie, H., Colahan, P. and Ott, E., 2005. Evaluation of electroacupuncture treatment of horses with signs of chronic thoracolumbar pain. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 227(2), pp.281-286.

- Biermann, N., Rindler, N. and Buchner, H., 2014. The Effect of Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields on Back Pain in Polo Ponies Evaluated by Pressure Algometry and Flexion Testing—A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 34(4), pp.500-507.

- Buchner, H., Zimmer, L., Haase, L., Perrier, J. and Peham, C., 2017. Effects of Whole Body Vibration on the Horse: Actual Vibration, Muscle Activity, and Warm-up Effect. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 51, pp.54-60.

- Adair, H. and Levine, D., 2019. Effects of 1-MHz Ultrasound on Epaxial Muscle Temperature in Horses. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 6(177).

- Gomez Álvarez, C., L’Ami, J., Moffatt, D., Back, W. and Van Weeren, P., 2008. Effect of chiropractic manipulations on the kinematics of back and limbs in horses with clinically diagnosed back problems. Equine Veterinary Journal, 40(2), pp.153-159.

- Stubbs, N., Kaiser, L., Hauptman, J. and Clayton, H., 2011. Dynamic mobilisation exercises increase cross sectional area of musculus multifidus. Equine Veterinary Journal, 43(5), pp.522-529.

- Holcombe, S., Shearer, T. and Valberg, S., 2019. The Effect of Core Abdominal Muscle Rehabilitation Exercises on Return to Training and Performance in Horses After Colic Surgery. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 75, pp.14-18.

- Denoix, J. and Pailloux, J., 2011. Communication and Relaxation. In: J. Denoix and J. Pailloux, ed., Physical Therapy and Massage for the Horse, 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp.83-88.

- Gomez Álvarez, C., Rhodin, M., Bobbert, M., Meyer, H., Weishaupt, M., Johnston, C. and van Weeren, P., 2006. The effect of head and neck position on the thoracolumbar kinematics in the unridden horse. Equine Veterinary Journal, (S36), pp.445-451.

- Denoix, J., 2013a. Lowering of the neck. In: J. Denoix, ed., Biomechanics and Physical Training of the Horse, 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp.52-61.