Digestion, Diseases & Conditions, Featured

How can we prevent gastric ulcers in horses?

Briony Witherow, examines the nutritional management of EGUS in horses

For every new piece of research on gastric ulcers, it appears the prevalence is only ever increasing; the key message being that ulcers can occur in all ages, breeds, and types of horses – not just the stereotypical poor doer. As owners and carers, we should all be aware of the signs and management strategies to reduce the risk of gastric ulcers in horses.

What are gastric ulcers in horses?

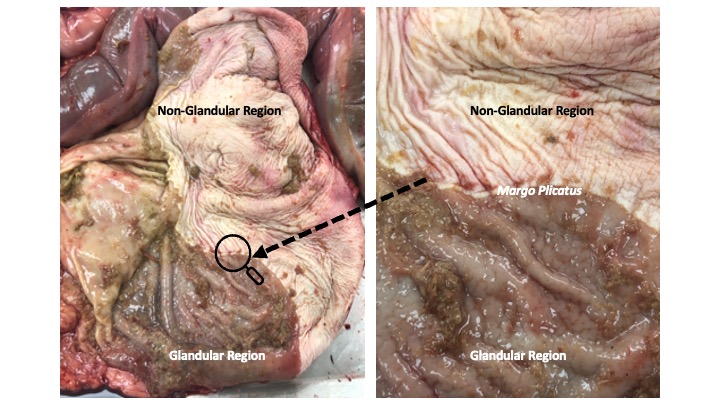

Equine gastric ulcer syndrome (or EGUS) is an umbrella term used to describe ulcerative diseases of the stomach (including the end of the oesophagus and start of the small intestine¹. Specific terms have more recently been developed which refer to the affected regions (see Figure 1)

- Equine squamous gastric disease (ESGD) for ulcers primarily affecting the non-glandular ‘unprotected’ (top) region of the stomach.

- Equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD) for ulcers primarily affecting the glandular region (bottom) of the stomach ² ³ ⁴ ⁵ .

The glandular region contains glands which secrete pepsin and hydrochloric acid continuously to breakdown food; it also has a mucosal layer that secretes bicarbonate, forming a protective layer to prevent the acid from damaging the stomach lining. Evidence of this mucosal layer can be seen in the figure above. The squamous or non-glandular region at the top of the stomach has no glands to protect the lining from harmful acid. This region acts as a reservoir for food as it makes it way to the glandular region. As there is no mucus or bicarbonate protection in its lining, this region instead relies on an almost continuous supply of fibrous material entering the stomach to act as a physical barrier against acid exposure (a bit like putting a lid on a bucket of acid to stop it slopping out). In terms of prevalence, most gastric ulcers in horses (80%) occur in the top third of the stomach (squamous region) with 20% occurring in the bottom two thirds (glandular region) ⁶ ⁷.

Why is a more specific diagnosis important?

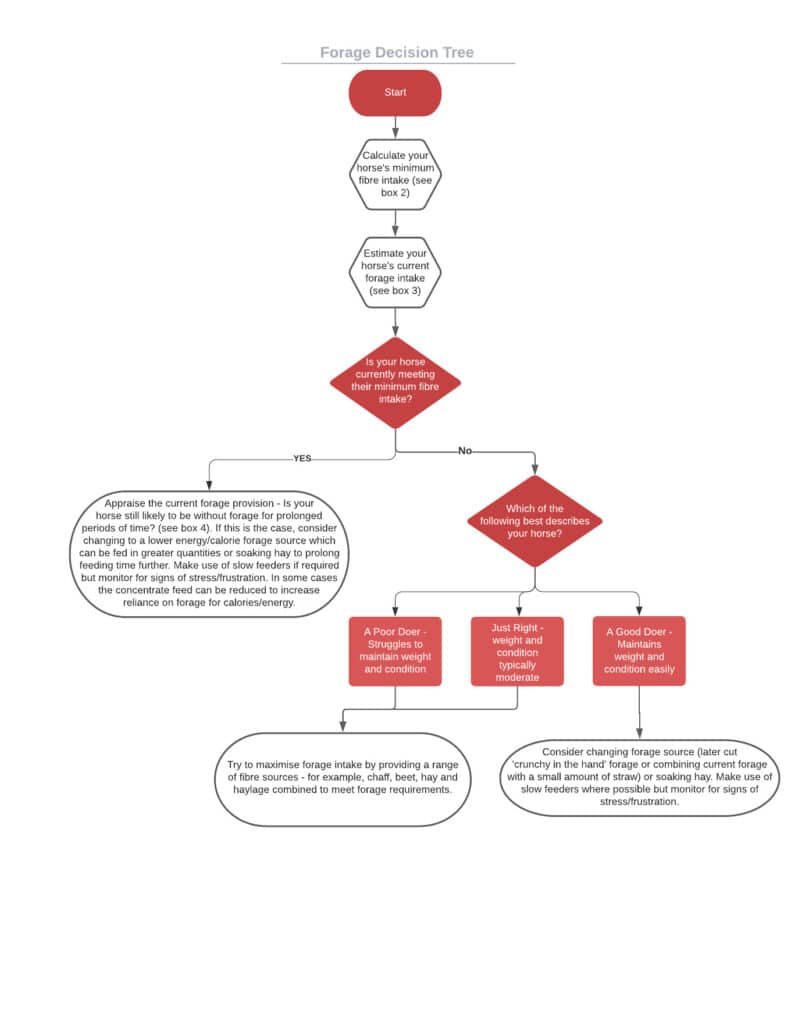

Differentiation between the two categories of ulceration is essential as risk factors and subsequently management vary. Gaining a clearer picture of the primary location of ulcers will ultimately help to make strategies for treatment, management and, prevention more tailored. As such, wherever possible when caring for a horse with a history of ulcers, good information on the location, number and severity of the lesions is key. Specific risk factors for ESGD and EGGD are outlined in ‘Equine Gastric Ulcers: The Facts’. Nutritional intervention Reducing the risk of gastric ulcers requires a holistic approach, considering not only medical intervention (if required) but also feed management changes. See ‘Equine Gastric Ulcers” The Facts’ for a list of key dos and don’ts and, use the decision trees below as a starting point for making informed feed choices.

Preventing gastric ulcers in horses

Step one: Assess the forage

How to calculate minimum fibre intake

All horses in normal work require an minimum of 1.5% of their bodyweight of fibre (this can include hay, haylage and grass) in dry matter per day.

Multiply your horse’s bodyweight (kg) by 0.015 to get w% of their bodyweight. For example, 500kg*0.015 = 7,5kg dry matter

Once you have your minimum forage amount in dry matter (above) divide this by 0.9 for hay and 0.6 for haylage (average dry matter values). This will give you the absolute minimum amount needed per day when this forage is your horse’s sole fibre source. Remember: this is the minimum quantity required – those in work needing weight and/or condition / energy, can be fed forage on an ad lib basis.

How to estimate current forage intake

Write down how much hay/haylage, grazing and any other significant fibre sources in the ration (chaff/beet). As minimum forage requirement is calculated in dry matter, we need to make sure we convert all these values to dry matter so that they are comparable. Estimate how long your forage may be occupying your horse.

Time how long it takes your horse to eat a set amount of their forage ration (1 or 2kg) depending on how much time you have.

Repeat this over a few days and you should have a rough estimate of how much time a set amount of forage may last. Using this information, you can gauge whether a slow feeder or, some other management to extend eating time may be beneficial.

Step 2: Assess the bucket feed

How to calculate ideal maximum combined starch and sugar intake from concentrate feed

Research suggests that the combined amount of starch and sugar from concentrate feed PER DAY should not exceed 2g per kilogram bodyweight or 1g per kilogram bodyweight per meal⁸. To calculate use the formula below:

Multiply your horse’s weight in kg by 2 to give max starch and sugar combined concentrate feed in GRAMS PER DAY; For a meal rate just use 1 times horse’s bodyweight to calculate the grams per feed.

Example: a 500kg horse fed two meals per day should not have more than 1000g starch and sugar combined PER DAY and 500g PER MEAL (when fed twice per day).

Please note it is vital to obtain an accurate starting weight of the horse, when calculating minimum feed required to reduce bodyweight. *Note that feeds holding the BETA Gastric Ulcer Mark have already been through a screening process, which confirms that when fed at the recommended rates, the combined starch and sugar intake does not exceed the daily and per meal values estimated by research to increase ulcer risk.

How to calculate current starch and sugar intake from concentrate feed

When trying to interpret what is low enough, make sure you are considering the quantities the product is intended to be fed at, not just the percentage of starch or sugar on the packaging or product literature.

Take home points on preventing gastric ulcers in horses

- When approaching feeding and nutrition to reduce the risk of gastric ulcers in horses, always take a holistic view. What does the horse’s management look like?

- Are there any factors which may inadvertently be causing stress, such as a lack of social interaction, time without forage or a stressful exercise regime?

- Reducing ulcer risk comes from overall management (reducing exposure to stress) and the fundamentals of the diet – sufficient fibre and low starch and sugar intakes.

- Try to view supplements as they are intended – the ‘cherry on top’ not the foundation.

While veterinary intervention in the treatment of EGUS is often an essential part of the approach, long term treatment and prevention strategies for both EGSD and EGGD should involve significant dietary and management changes.

References

- Andrews, F., Bernard, W., Byars, D., Cohen, N., Divers, T., MacAllister, C., McGladdery, A., Merritt, A., Murray, M., Orsini, J., Snyder, J., and Vatistas, N. (1999) Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS). Equine Veterinary Education, 11 (5): 262-272

- Sykes, B.W., and Jokisalo, J.M. (2014) Rethinking equine gastric ulcer syndrome: Part 1- Terminology, clinical signs and diagnosis. Equine Veterinary Education, 26 (10) 543-547

- Sykes, B.W., and Jokisalo, J.M. (2015a) Rethinking equine gastric ulcer syndrome: Part 2- Equine squamous gastric ulcer syndrome (ESGUS). Equine Veterinary Education, 27 (5) 264-268

- Sykes, B., and Jokisalo, J.M. (2015b) Rethinking equine gastric ulcer syndrome: Part 3 – Equine glandular gastric ulcer syndrome (EGGUS). Equine Veterinary Education, 27 (7): 372-375

- Sykes, B.W., Hewestson, M., Hepburn, R.J., Luthersson, N., and Tamzali, Y. (2015) European College of Equine Internal Medicine Consensus Statement – Equine gastric ulcer syndrome in adult horses. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 29 (5): 1288-1299

- Bell, R.J.W., Kingston, J.K., Mogg, T.D., Perkins, N.R. (2007) The prevalence of gastric ulceration in racehorses in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 55 (1): 12-18 7. Reese, R.E., and Andrews, F.M. (2009) Nutrition and dietary management of equine gastric ulcer syndrome. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 25 (1): 79-92

- Luthersson, N., Nielsen, K., Harris, P., and Parkin, T.D.H. (2009) Risk factors associated with equine gastric ulceration syndrome (EGUS) in 201 horses in Denmark. Equine Veterinary Journal, 41 (7): 625-630