Edward Busuttil asks – is the tail more than just a fly swatter?

We have all been there, standing by a horse’s hindquarters, giving their bum a scratch before WHACK, out of the blue, we receive a slap in the face and mouthful of a mucky tail. This is generally followed by a ‘Thanks for that’ and a swift step towards the horse’s front end, questioning why horses even need a tail.

To get a better understanding of the importance of the tail, it is important to understand both the anatomy and the different types of muscles in the tail.

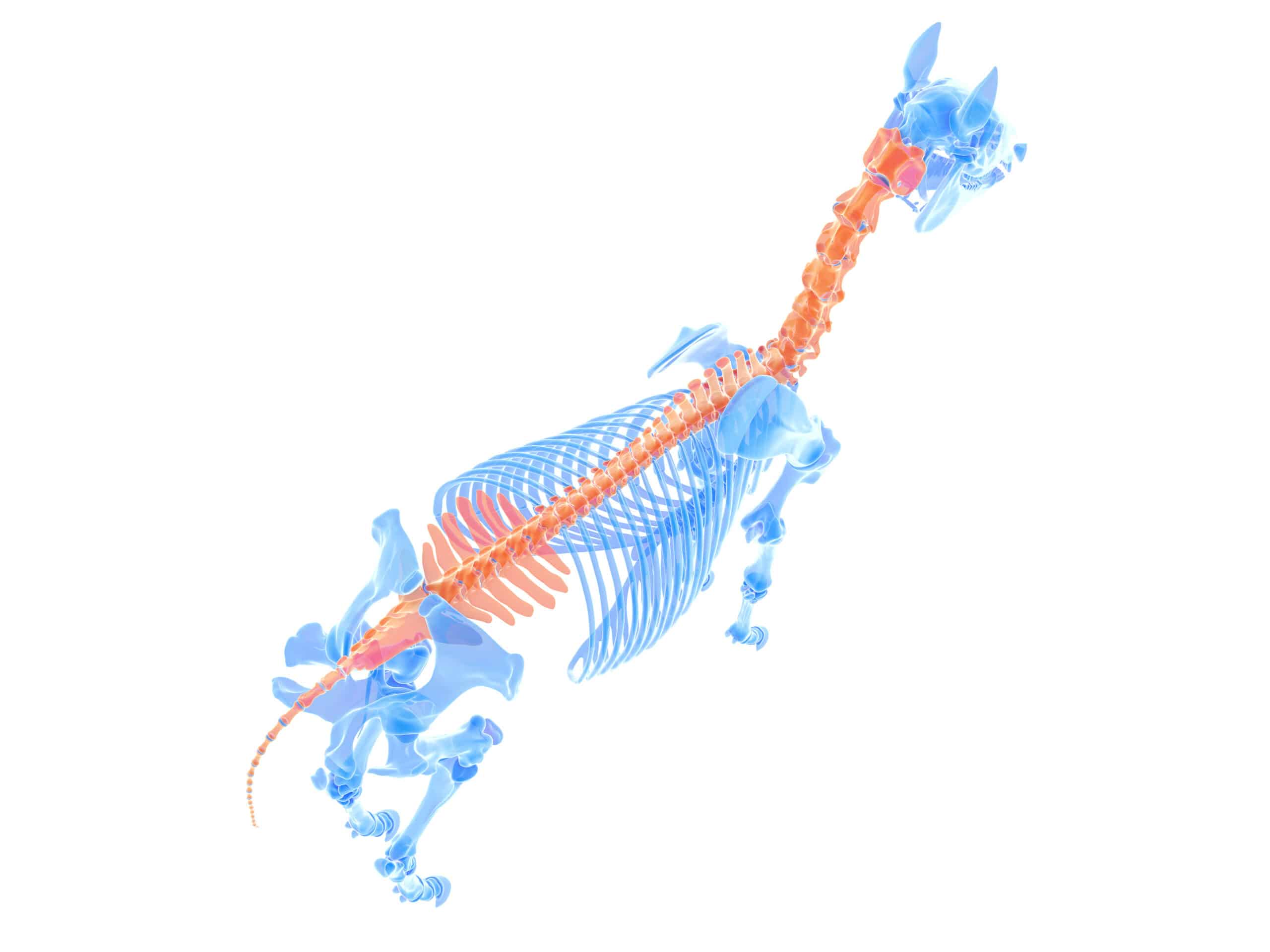

The anatomy

A horse’s tail has on average, 18 bones and, as it is a continuation of the spine, they are called coccygeal vertebrae. The vertebrae in this region are very different from the rest of the spine, with very thick discs present between each one.

How does the tail move?

A number of muscles are involved in the movement of the tail; these mainly include the coccygeues and, the dorsal and ventral sacrocaudalis muscles. The sacrocaudalis muscles are again subdivided into medial and lateral components. The coccygeus muscle connects the sacrotuberous ligament (a broad ligament originating from the sacrum and tuber sacrale that inserts onto the tuber ischium, providing stability to the pelvis) to the first few coccygeal vertebrae. The muscles in the tail are surrounded by a thick fascia.

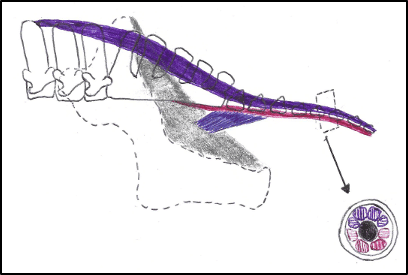

The tail is mainly moved in an upward-downward direction by the coccygeus, and side to side by the sacrocaudalis muscles.

The sacrocaudalis dorsalis (purple) is subdivided into the medial (vertical lines) and lateral (horizontal lines). Sacrocaudalis ventralis (red) is also subdivided into medial and lateral components, and the coccygeus (blue). Note the thick tail fascia surrounding the muscles in the tail in the cross-sectional drawing.

Different types of muscles

Muscles can be subdivided into locomotory (creating movement) or postural (maintaining position). Some muscles have a dual function, therefore responsible for both locomotion and posture.

What determines whether a muscle is locomotory or postural?

This is determined by the type of muscle fibres in the specific muscle. Locomotory muscles have a lot of fast twitch muscle fibres, whereas postural muscles are mainly composed of slow twitch muscle fibres.

Why is this important in the tail?

The medial sacrocaudalis dorsalis is mainly slow twitch, and therefore postural, whereas the lateral sacrocaudalis is mainly fast twitch. The sacrocaudalis ventralis has dual function¹. This means that specific regions in the tail (namely the medial sacrocaudalis dorsalis) are directly responsible for maintaining posture, and therefore play a key role in balance, not only of the tail, but the whole body.

What does a normal tail look like?

As the tail has a role in balance, a healthy tail should sit loosely, and centrally between the hamstrings.

The horse should try to clamp its tail downwards when it is manipulated, or when you are trying to dress it with a bandage. When moving at the walk and trot, the tail should wave from side to side in a symmetric manner².

What can the tail’s position tell us about the horse?

So, we have already established that the tail can be used as a weapon with pin-point accuracy but, what more can the tail’s position tell us about our horses? A 2020 study², showed that although not always indicative of lameness, horses which held their tails to the side (and therefore had a crooked tail) were more likely to be lame. They found that the lameness was most likely to be due to a hindlimb lameness, sacroiliac discomfort or, horses with increased tension in the muscles in their back behind where the saddle sits.

The study also revealed that a crooked tail could be a sign of forelimb lameness and, that the side that the tail was held in was not necessarily related to the side of the lameness. Therefore, a horse holding its tail to the left might be completely sound, or be lame through its right forelimb.

A crooked tail can also be present during exercise, both in hand or when the horse is ridden. Under saddle other signs of discomfort such as tail swishing, lashing and clamping, may also be present as signs of discomfort³. Although nerve and joint blocks stopped the tail action during ridden work⁴, diagnosing the lameness did not immediately correct the crooked tail carriage².

Conclusion

If your horse has suddenly developed a crooked tail, or started to swish its tail under saddle, it might be worth consulting with your veterinarian, chiropractor, osteopath or physiotherapist. Looking back at videos of ridden work can be a key indication of whether discomfort is developing; getting a baseline understanding of what your horse’s tail usually looks like when in different gaits can help you act quickly and, prevent longer periods of rehabilitation.

References

- Hyytiäinen H, Mykkänen A, Hielm-Björkman A, Stubbs N, McGowan C. Muscle fibre type distribution of the thoracolumbar and hindlimb regions of horses: relating fibre type and functional role. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 2014;56(8).

- Hibbs, K., Jarvis, G. and Dyson, S., 2020. Crooked tail carriage in horses: Increased prevalence in lame horses and those with thoracolumbar epaxial muscle tension or sacroiliac joint region pain. Equine Veterinary Education

- Dyson, S., Berger, J., Ellis, A. and Mullard, J., 2018. Development of an ethogram for a pain scoring system in ridden horses and its application to determine the presence of musculoskeletal pain. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 23, pp.47-57.

- Dyson, S. and Van Dijk, J. (2020) Application of a ridden horse ethogram to video recordings of 21 horses before and after diagnostic anaesthesia: reduction in behaviour scores. Equine Vet. Educ. 32 Suppl. 10