Dr Graham Hunter outlines the anatomy of this amazing joint that flexes and extends the hind leg

A horse’s stifle is a very large and complex joint, the largest and most elaborate of all the equine joints. It is an example of a ginglymus, which is a hinge joint that allows movement in only one plane. The stifle joint functions to flex and extend the hind leg, moving the horse forward. In the normal standing position, the articular angle of the stifle between the femur (thigh bone) and tibia (gaskin) is about 150 degrees. Flexion is limited only by contact between the thigh and the limb below the stifle. When extended, the joint cannot be extended to form a straight line through it.

There are 3 main bones involved in the stifle

- The femur,(thigh bone)

- The patella (kneecap)

- And the tibia (gaskin)

There are 3 large joints in the stifle

- The femoropatellar joint

- The medial femorotibial joint

- And the lateral femorotibial joint

There are 14 ligaments in the stifle

- The medial and lateral collateral ligament

- The cranial and caudal cruciate ligaments

- Three patellar ligaments (the medial middle and lateral)

- The medial and lateral femoropatellar ligaments

- The cranial ligaments of the menisci

- The meniscofemoral ligament

- And the caudal ligament of the medial and lateral meniscus

There are also two cartilaginous pads called the meniscii, that sit between the femur and the tibia.

The femoropatellar joint

The femoropatellar joint is the largest fluid filled joint in the horse’s body .This articulation is formed between two cartilage covered ridges (trochlear ridges) with a groove in the middle (trochlear groove) and the underside of the patella (kneecap). The trochlear ridges are different sizes and lie at a slightly oblique angle. The outside (lateral) ridge is narrower than the inside (medial) ridge. The medial (inside) ridge is larger especially at the upper (proximal) aspect. The lateral (outside) ridge is the most common site for osteochondrosis (OCD) in the stifle.

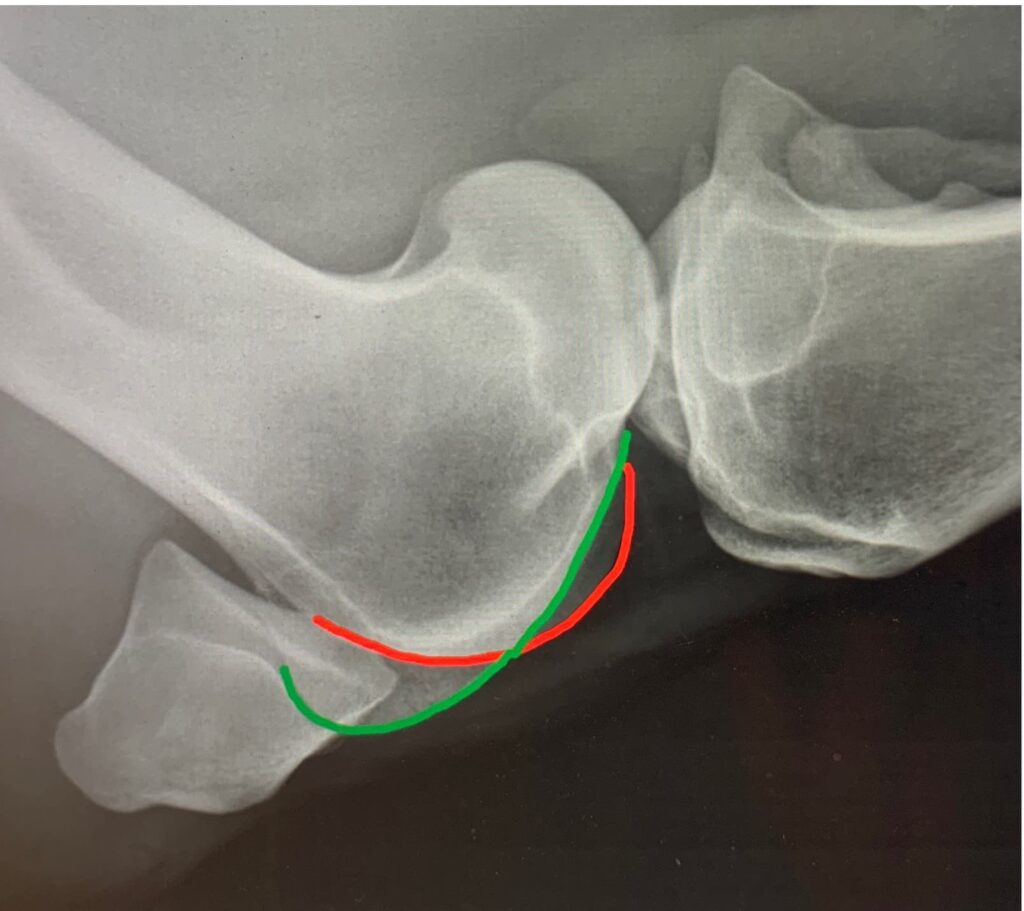

Figure 1. An x-ray demonstrating the larger medial trochlear ridge in green and the smaller lateral trochlear ridge in red.

Figure 2. An x-ray taken from above looking down which shows the patella and the two trochlear ridges of the femur. Note how much bigger and wider the medial ridge (green) is compared to the sharper narrower lateral ridge (red).

Figure 3. Osteochondrosis of the lateral (outside) trochlear ridge of the femur.

Figure 4. A keyhole camera view of badly damaged cartilage on the lateral trochlear ridge of the femoropatellar joint. This is an example of osteochondrosis (OCD).

The patella (kneecap) is a completely separate bone that attaches to the quadriceps femoris muscle at the top (proximally) of this bone and patellar ligaments at the bottom (distally). These patellar ligaments attach the bottom of the patella to the front of the upper (proximal) tibia.

Ligaments of the femoropatellar joint

There are 5 ligaments in the femoropatellar joint. They are the medial (inside) and lateral (outside) femoropatellar ligaments and the 3 patellar ligaments, the middle, lateral and medial patellar ligaments. The femoropatellar ligament is show in Fig 5, drawn in orange. The medial (inside) ligament is positioned exactly opposite the lateral (outside) ligament.

Figure 5. The medial and lateral femoropatellar ligaments are identically placed on the inside and the outside of this joint and originate on the side of the patella and insert onto medial and lateral epicondyles (specifically named boney lumps) of the distal femur.

There are three patellar ligaments which are named the medial (inside) middle and lateral (outside) patellar ligaments. They connect the patella to the front of the upper (proximal) tibia.

There is a supplementary plate of cartilage on the medial (inside) aspect of the patella which curves over the medial (inside) trochlear ridge of the femur. This is coloured red in Fig 5 . It is the controlled hooking of this cartilage extension over the medial trochlear ridge that forms part of the ‘passive stay apparatus’. This is the apparatus that allows the horse to lock the limb with no muscular effort allowing the horse to rest the opposite hindlimb. The inappropriate locking or catching of this cartilage extension of the patella causes ‘upward fixation of the patella’ or ‘delayed patellar release’.

Figure 6. This shows the cartilage (red) hooking over the medial trochlear ridge and also demonstrating the 3 patellar ligaments.

The femorotibial joints

The medial (inside) and lateral (outside) femorotibial joints are separate joint pouches formed between the condyles (knuckles) of the lower femur and the upper (proximal) aspect of the tibia. The tibia is not adapted to the shape and curve of the condyles of the femur. Like the trochlear ridges of the femoropatellar joint, the condyles of the distal femur are orientated in a slightly oblique manner. This results in the leg rotating slightly when flexed.

Figure 7. The medial (inside) femoral condyle of the distal femur is marked in green and the lateral (outside) femoral condyle of the distal femur -is marked in red

The joints often interconnect. The medial femorotibial joint communicates with the femoropatellar joint in around 70% of horses. The communication is via a small slit-like opening between the medial femorotibial joint and the lowest part of the medial trochlear ridge of the femoropatellar joint. In 30% of horses there is a communication between the lateral femorotibial and the femoropatellar joint. The communication again is via a small slit-like opening between the lateral femorotibial joint and the lowest part of the lateral trochlear ridge of the femoropatellar joint. There is rarely a communication between the medial and the lateral femorotibial joints at all.

The MICET The small boney mountain range in the middle of the tibial part of the joint is called the ‘spine of the tibia’, with the large medial (inside) peak called the medial intercondylar eminence of the tibia or the ‘MICET.’ The MICETserves as an attachment site for one of the main stabalising ligaments, the anterior cruciate ligament. This can occasional fracture off and can also change shape in cases of osteoarthritis.

Figure 8: Medial intercondylar eminence of the tibia (MICET) – red Intercondylar fossa, the space between the two condyles – green

Figure 9: An inside view of what the MICET (T) looks like. The medial condyle can also be seen (C), as well as the anterior cruciate ligament (L)

The meniscii

There are two main cartilage discs called meniscii or semilunar cartilages in the stifle which sit between the lower femur and the upper tibia. These cartilage crescent shaped discs are shaped in such a way as to give a perfect fit to these bones allowing them to move smoothly together for perfect motion. The menisci are concave on the upper surface and much flatter on the lower surface to sit on the flatter tibial plateau. The outside edges of each menisci are thick and convex and the inner edges of the crescent cartilage are thin and concave.

Figure 10: Demonstrating the two menisci. L, lateral menisci, M, medial menisci.,Cr Cranial cruciate ligament, Ca, Caudal cruciate ligament., CrM, Cranial ligaments of the menisci, CaM, caudal ligament of the menisci. MF, meniscofemoral ligament. Pink, spine of the tibia (MICET)

The fibrous ends of the meniscii form ligaments which are attached to the front and back of the spine of the tibia. The back of the lateral (outside) meniscus has a further meniscofemoral ligament which inserts on the back part of the intercondylar fossa of the femur, the space between the two condyles. See Fig 8.

The cranial cruciate ligament originates just to the side of the MICET and extends upwards and back to insert onto the lateral (outside) wall of the intercondylar fossa. The caudal cruciate is much larger and sits on the inside of the cranial cruciate. It originates from a small notch, called the popliteal notch, on the back of the proximal (upper) tibia and extends upwards and forwards inserting at the front of the intercondylar fossa.

Figure 11: Medial collateral ligament red, head of the fibula – blue

There are two main ligaments which have not been mentioned yet. They are the medial and lateral collateral ligaments. The medial collateral ligament originates from the medial epicondyle (bone protuberance) of the femur and inserts just below the medial condyle of the tibia. The lateral collateral ligament from the lateral epicondyle and inserts on the head of the fibula (the second vestigial bone in the gaskin). See Fig 11. These ligaments along with the cruciate ligaments are the main stabalising structures holding the whole stifle together so that it can do its job in smoothly flexing and extending , coping with huge forces as the horse is propelled forward.